VOR Approaches - Part II

VOR approaches with the station off the field have the advantage that an electronic fix, the Final Approach Fix, is available to provide exact time and distance information to the airport. For this reason, some pilots prefer that type of VOR approach over one where the VOR is on the field, where precise time and distance information to the field is not available.

Of course, if the Omni station has DME capability and a DME is available in the aircraft, then time and distance information to the station, or the field, would be available.

The approach procedures described here assume no DME capability.

VOR approaches flown when the station is on the field have two advantages over the others, though. First, the VOR sensitivity increases as one nears the VOR, or field. This should place the aircraft nearer to the desired final approach position.

Second, there is no ambiguity on the MAP, Missed Approach Point. When the VOR is off the field, the pilot must determine the MAP point by measuring time from the FAF. In the case of the VOR on the field, the TO-FROM flag will switch from the TO position to the FROM position. At that point if the runway is not in sight, the pilot must execute a Missed Approach Procedure.

With the flight experience obtained from the previous practice sessions, these approach procedures will be easy.

Runway Visibility Range

A number of years ago, the FAA decided that visibility figures didn't accurately report how far down a runway a pilot could see from a moving aircraft. They developed a new criteria which better specified the visibility down a runway; called Runway Visibility Range, or RVR. In many instances approach plates now report visibility minimums in RVR.

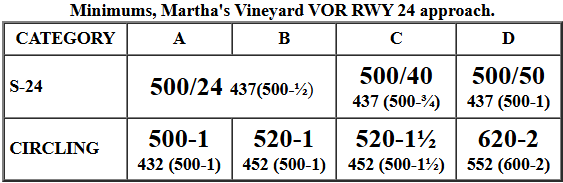

Look at the table of minimums on a Martha's Vineyard approach plate.

Notice the first entry under Category A and B for the S-24 approach, the straight-in to Runway 24 at Martha's Vineyard airport. It is "500/24." The 500, of course, is the Minimum Descent Altitude, MDA. Can't go below that altitude unless the runway or approach lights are in sight and a normal landing can be made.

A "24" appears after the slash indicating that a minimum of 2400 feet RVR is required to land for S-24. The RVR is specified on an approach plate in hundreds of feet. If you were flying a Category-C aircraft, your RVR requirement is 4000 ft., and 5000 ft. for Category D.

Well, all that is nice to know. When you look at the minimums on your approach plates, you'll now understand that sometimes statute miles visibility requirements are specified and at other times the RVR requirements are shown, and you'll recognize each.

Unfortunately, that's as far as Microsoft lets you go, is to understand the information. Flight Simulator only lets you select visibility in statute miles. Maybe a future patch will fix that.

There are two ways to convert the RVR to statute miles to enter the proper information into the flight simulator: First, you could divide the RVR by the 5280 ft. in one mile. For a 2400 ft. RVR, that would give you 0.45 mi. which you would round up to 0.5 mi.

The second, and simpler way, is to look at the military numbers on the approach plate. Jump to the second set of numbers, specifically those enclosed by parenthesis. Again for Categories A and B, the military numbers are "(500-½)." The military requirement is 500 ft. ceiling with one-half mile visibility. From this you now know to enter one-half mile visibility into your flight simulator for these two categories. Category C would be ¾ mile visibility and Category D would be 1 mile visibility.

A 2400 ft. RVR is so common that you will quickly learn to enter one-half mile visibility into your flight simulator for that situation.

The visibility minimums for the circling approach are always given in miles.

* * *

I was on short final to Nantucket's Runway 24. The weather was at minimums for the VOR approach; 420 ft. ceiling, solid overcast, heavy fog with a 2400 ft. runway-visibility-range. Now at the MDA, my windshield was brushing at the clouds while I mucked about in and out of the scud, trying to keep on course.

I was on short final to Nantucket's Runway 24. The weather was at minimums for the VOR approach; 420 ft. ceiling, solid overcast, heavy fog with a 2400 ft. runway-visibility-range. Now at the MDA, my windshield was brushing at the clouds while I mucked about in and out of the scud, trying to keep on course.

What lousy weather, even the birds must be walking.

I nearly jumped out of my skin when an alarm sounded in the cabin. Quickly glancing around, I searched for the source of trouble. Then the racket stopped. Returning my gaze to the gauges, the aircraft was still doing well; heading right on the money and altitude on the MDA. MAP was in forty-five seconds. If the approach lights didn't show soon, it was going to be a Go-Around.

The alarm sounded again, more insistent. I cursed to myself. It was my cellphone in my flight bag. I had forgotten to turn it off. If I had the time and altitude, I'd have opened the canopy and sent that phone sailing into Buzzards Bay. There was nothing I could do now but put up with it. It was a distraction I didn't need as it continued to ring.

Then the runway appeared and I greased on a landing. As I turned off the runway, the ringing stopped.

The caller caught up to me as I was asking the line-boy to fuel the aircraft. I dug into my flight bag, retrieved the phone, and answered it. Counter was on the other end.

"Good Day to you," he boomed, as if sunning himself on the Riviera. "How convenient that you're at Nantucket. I'm here, too."

"And where might that be," I asked, trudging to the terminal, the mist seeping through my clothes.

"A cab's bringing me out now. Your boss said I could catch you there, that you wouldn't mind a short hop to Martha's Vineyard."

"What's going on in the Vineyard," I asked, glancing above at the darkening skies.

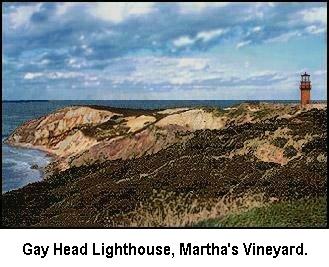

"The lighthouses, of course. It's the lighthouses," Counter replied. "I watched A Stolen Life on The Late Movie last night. Great Bette Davis movie! Great special effects! The story was around a Martha's Vineyard lighthouse. Martha's Vineyard has five of 'em, you know. And the best, I hear, is Gay Head.

"The weather's not looking good," I tried.

"Nonsense! I'm packed, checked out of the hotel, got my bag with me, and everything." He responded. " I'm almost there. What better time to look at lighthouses and listen to fog horns then on a foggy day?" he asked.

"I don't think there have been any fog horns working for years," I said, with a glimmer of hope.

"Doesn't matter. That Gay Head light is one important light. It sits 170 feet above the sea on clay bluffs on the Western side of Martha's Vineyard. That's where the Devil's Bridge rocks threaten the entrance to Vineyard Sound, the main route to Boston Harbor from the south."

"Did you know that a lighthouse could be too high?" Counter went on. "Yep, he replied," before I could get a word in. "Gay Head was so high at first that it shone above the fog. Didn't help the ships very much. It's been up and down like an elevator ever since, designers trying to find the best height."

"There was a big shipwreck nearby in 1884. I heard 120 people drowned. I want to go there and learn more," Counter ended.

"Let me check the weather on the Vineyard, see if it's as bad as it is here," I said.

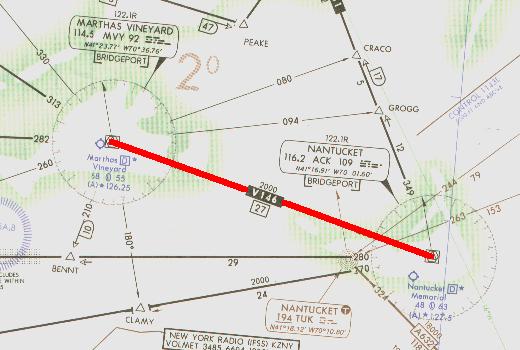

Nantucket, Massachusetts to Martha's Vineyard, Massachusetts.

Click on image for flight-information package.

The flight begins at Nantucket Memorial airport, Nantucket, Mass. with Martha's Vineyard, Mass. the destination. Click on the image above to download the flight-information package, ack-mvy.zip.

The zip-file includes the IFR chart, the approach plate for VOR Rwy 24 at Martha's Vineyard airport in Vineyard Haven, and this text description of the flight.

This is a straight-forward flight ending with an instrument approach at Martha's Vineyard, where the VOR is on the field. We proceed from Nantucket to the MVY VOR, fly outbound, execute a procedure turn, and return to MVY and Runway 24 at Martha's Vineyard.

There is a very difficult 128° right turn at MVY VOR when arriving from Nantucket to intersect the 067° radial to start the approach. We convert this into a simple maneuver with a left teardrop turn at MVY, coming back around to intercept the 067° radial.

As usual, do nothing until you have gone through the step-by-step details of the flight with this text and your charts. Only by doing this will you both understand the purpose of each step, but you will visualize them in your mind, a critical part of instrument flight.

NOTE: Fly this entire flight with your Nav-2 Receiver for better needle visibility.

- Set the flight simulator weather conditions to 800 ft overcast, cloud tops at 10,000 ft., and one mile visibility. The wind is calm.

- Move the aircraft to Nantucket's Runway 24, airport KACK, and retract the flaps to 0°.

- Tune Nav-2 receiver to Martha's Vineyard VOR, 114.5 MHz., ident MVY.

- Set the VOR-2 OBS to 299°. Reset the timer to zero.

- Takeoff from Runway 24 with a climbing right turn to 345°. ATC has cleared you to 4000 ft.

- Intercept Martha Vineyard's 299° radial northwest-bound, indicated by the VOR needle centering. Cruise at 110 kts.

- Track inbound 299° to the MVY VOR.

- As the needle centers and the FROM flag appears indicating station passage, start the timer and maintain your 299° heading for one minute. Change the OBS setting to 067°.

- Don't worry if the needle slides off the gauge on station passage, and don't chase it by altering your heading. Stay on course and the needle will return to dead center in a moment.

- At one minute after station passage turn left and come back around to intersect the 067° radial inbound to MVY VOR. The TO flag should be showing when the needle again centers.

- Stop and reset the timer on the return leg to MVY, but don't start it.

- At station passage, when the FROM flag appears, start the timer and fly outbound for three minutes descending to 1800 ft.

- Drop one notch of flaps and slow to 75 kts. while on the outbound leg.

It's vital to stabilize the approach well before beginning descent to the MDA.

- At three minutes, or slightly longer if you wish to be at 1800 ft. when beginning the procedure turn, turn right to 112°. If the outbound leg is more than three minutes, mentally note the time when starting the procedure turn. Be aware that you must remain within 10 nm. of the VOR during the approach procedure, which is only five minutes or so flying radius from the VOR at 110 kts. Time and distance allowances must be included for the procedure turn to stay within the 10 nm.

- Reset and restart the timer. Fly the 112° heading for one minute. Set the OBS to 247°, the inbound track to the VOR and to Runway 24.

- After one minute into the procedure turn, turn left to 292° to return to intercept the 247° inbound radial to the station.

- Reset but do not restart the timer.

- When the VOR needle centers, turn left and track inbound on the 247° radial.

- Start the timer, and descend to 500 ft., the MDA. Since you flew outbound for three minutes, expect station passage after three and a half minutes, or so, inbound. If the outbound leg was different than three minutes, add about a half-minute for the inbound leg to station passage. This will not be exact, but will provide a far better gauge of distance to the VOR then guessing.

- Keep the VOR needle centered with minor heading adjustments, but don't chase the needle.

- Be alert on this approach. With only one mile visibility, you will sight the approach end of the runway only 48 secs. before arrival at the threshold. The runway will be a bit off to the left because of the location of the VOR on the field.

- If the TO-FROM flag switches to FROM before or just as you sight the runway, immediately execute the Missed Approach Procedure shown on the approach plate— it's too late to land.

- Field elevation is 68 ft., hence you must descend 432 ft. after sighting the field. Chopping the power and dropping full flaps should put you in a good approach attitude, as well as allowing you to slow the aircraft even more. Do not point the nose of the aircraft down and dive for the field. A crash may result or the speed will be so high that you will float past the end of the runway. Flare normally and touchdown.

- Time: 32 minutes.

* * *

"Flying is too easy, today," Counter said, as I was gathering the items for our flight. He had out-done himself and scheduled this flight two days in advance. "Push a few buttons, and electronics take you from Point A to Point B," he went on. "As far as I can see, even a child could do it."

"Flying is too easy, today," Counter said, as I was gathering the items for our flight. He had out-done himself and scheduled this flight two days in advance. "Push a few buttons, and electronics take you from Point A to Point B," he went on. "As far as I can see, even a child could do it."

"Nothing to it," I replied, not looking for a debate. "It's so simple, sometimes I wonder why I even come along."

"You don't even look like a pilot," Counter said, moving in a different direction. "No scarf, no goggles, no helmet, no leather jacket."

"The Boss doesn't pay me enough to buy upscale stuff like that," I said, with a sigh.

"I may have to talk to him about that, he charges me big money. Let's get going—I can't wait to learn about some real pilots and the airplanes that they flew," Counter said walking out the door towards the aircraft.

"Well, you'll see plenty at The New England Air Museum at Bradley," I answered, catching up to him. "They have over 125 aircraft in their collection."

"I'm only interested in one plane and one pilot, actually—Louis Bleriot of France. He was the first to fly solo across the English Channel, from France to England. Did it in 1909," Counter said, his enthusiasm building. "In the Bleriot Monoplane X1."

"Yeah, he sure earned a reputation," I said.

"You bet he did. Taught himself how to fly, invented his own plane, and a monoplane instead of the biplanes that everyone else was fooling around with." Counter was getting excited. "Imagine, he won the £1000 prize from the London newspaper, the Daily Mail, for a 24 mile, 40 minute flight. That was $5000, had to be a good pilot."

"Worth about $100,000 today. He had his problems, though. Crashed his plane 51 times before the flight across the Channel," I added. "He even had a cast on his leg when he set the record with his famous flight."

"Yeah? Where'd you learn that? All I read was that his engine quit over the English Channel because it had overheated. Then a lucky rainstorm came up and cooled off the engine enough to restart and get him over the White Cliffs of Dover," Counter finished proudly.

"Well, you do know that he crashed when he landed on English soil?" I asked.

"Of course," Counter said, a bit defensively. "All the old pictures show that."

"That was crash number 52. That nameless soul had to have had Bleriot in mind when he coined the famous expression." I said, holding back a smile.

"What expression was that?" Counter asked suspiciously.

"Any landing that you can walk away from is a good landing."

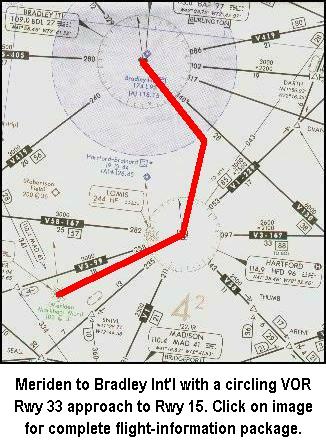

Meriden, Connecticut to Hartford, Connecticut.

The zip-file includes the IFR chart, the approach plate for VOR Rwy 33 at Bradley Int'l., and this text description of the flight.

This is another VOR approach not requiring a procedure turn. And, while the VOR for this approach is on the field, the Final Approach Fix is a VOR intersection providing the same valuable time and distance information to the field as if the VOR were off the field. It's sort of the best of both worlds.

On this flight you'll also use the DME to identify intersections.

To add to the challenge, this is a circling approach with a serious wind component. You will land on BDL's Runway 15, but use the approach procedure for Runway 33 and circle to land at Runway 15. You'll be busy.

Actually, it's a pretty straight-forward flight ending with a circling instrument approach at Bradley Int'l. where the VOR is on the field. We proceed from Meriden to the Hartford VOR, then to the CLEFF intersection, inbound to the WISOK intersection, the FAF, and then to the airport, circling around to land on Runway 15.

As usual, do nothing until you have gone through the step-by-step details of the flight with this text and your charts. Only by doing this will you both understand the purpose of each step, but you will visualize them in your mind, a critical part of instrument flight.

NOTE: Fly the Instrument Approach portion with your Nav-2 Receiver for better needle visibility.

- Set the flight simulator weather conditions to 900 ft overcast, cloud tops at 10,000 ft., and two miles visibility. Set the wind to 20 kts. from 175°.

- Move the aircraft to Meriden's Runway 18, KMMK, and retract the flaps to 0°.

- Tune Nav-1 receiver to Hartford VOR, 114.9 MHz., ident HFD. Fly the first leg with Nav-2.

- Set the VOR-1 OBS to 070°. Reset the timer to zero.

- Switch the DME to Nav-1, HFD VOR. KMMK is 14.9 NM from the VOR.

- Tune the Nav-2 receiver to Bradley VOR, 109.0 MHz, ident BDL.

- Set VOR-2 OBS to 329°.

- Fly Nav-2. Takeoff from Runway 18 with a climbing left turn to track 070° to HFD. ATC has cleared you to 5000 ft.

- Climb at 90 kts. While climbing, the WCA will be 12° to the Right. Monitor your progress with the DME.

- At 110 kts. cruise, the WCA is 10° to the Right.

- On station passage at HFD, when the FROM flag appears, turn left to magnetic course 021° and set the VOR-1 OBS to 021°. The WCA will be about 4° to the Right.

- Descend to 3000 ft. CLEFF Intersection is 10.3 NM beyond HFD VOR.

- Fly Nav-2. When the VOR-2 needle centers, you are at CLEFF intersection, 10.2 nm. from the field.

- Turn left to the 329° magnetic course heading inbound to the VOR and start the timer. You will have an 18 kt. tailwind and need a 7° WCA to the Left at 75 kts.

- Switch your DME to Nav-2 which should show about 10 NM from BDL VOR on the field.

- Descend to 1900 ft. Drop one notch of flaps and slow to 75 kts.

- WISOK Intersection, your FAF, is 6 DME from BDL VOR.

- When the DME shows 6.0 you are at WISOK intersection, the FAF, 5.1 nm to the station and field.

- Reset and restart the timer, and descend to 680 ft.

- With the 18 kt. tailwind your ground speed will be 98 kts. It is 3 min., 17 secs. to the threshold of Runway 33.

- With two-miles visibility, you should spot the runway in 2 min., 00 secs. This is the opposite end of your landing runway.

- On sighting Runway 33, directly move to the right to enter the 330° left downwind leg for Runway 15.

- Do not drift into the clouds. If you do, you must immediately execute a missed approach.

- The Left base leg is 240° with a 14° Left WCA. Turn final approach and land normally after configuring the aircraft for landing. Your ground speed on final will be 57 kts.

- Time: 26 minutes.

This flight shows how helpful a second VOR and DME can be during an instrument flight.

* * *

The Boss had a good year last year—business was up strongly. He was even considering hiring another pilot and leasing another Cessna Nav Trainer.

It must have been a good year, because I was on my way to Bridgeport to pick up new electronics for the fleet. We were going all digital. I think Mr. Counter had something to do with that. He talked about other charter companies being more modern and maybe that's where his business belonged.

That got The Boss's attention real fast. One final leg and I'd be in Bridgeport. The weather wasn't cooperating well, but at least it was above minimums, if only barely.

What made this flight particularly enjoyable was that I had left my pager and cellphone back home. It would be almost impossible to interrupt my schedule.

I finished the flight planning, had gotten the weather, filed an IFR flight plan for Bridgeport, and pre-flighted the aircraft. I was ready to go. The engine came up smoothly when I started it, and the gauges all looked good. Chester is not a controlled field, so I dialed up UNICOM to announce my intentions to depart.

As I was taxiing out to the runway, UNICOM called back and asked if I could take a message from a Mr. Benjamin Counter. I reported that their transmission was breaking up, must be a bad mic., but I would check back when airborne. I opened the throttle and was quickly in the air.

Chester, Connecticut to Bridgeport, Connecticut.

Click on image for flight-information package.

This third flight will be easy. You've been through a host of new procedures up to this point and it's time for a VOR approach that's "fun." The flight begins at Chester airport, 3B9 (KSNC in FSX), in Chester, Connecticut with a destination of Igor Sikorsky Memorial airport, KBDR, in Bridgeport, Connecticut. The approach will be to Runway 24. Click on the image above to download the flight-information package, chstr-bdr.zip. The zip-file includes the IFR chart, the approach plate for VOR Rwy 24 at Bridgeport, and this text description of the flight.

This is another VOR approach not requiring a procedure turn and also one where the FAF is a VOR intersection. We proceed from Chester airport to the Madison VOR, then to the BAYYS intersection, inbound to the MILUM intersection, the FAF, and then to the airport with a straight-in landing to Runway 24. Again, you'll use your DME.

As usual, do nothing until you have gone through the step-by-step details of the flight with this text and your charts. Only by doing this will you both understand the purpose of each step, but you will visualize them in your mind, a critical part of instrument flight.

NOTE: Fly the Instrument Approach portion with your Nav-2 Receiver for better needle visibility.

- Set the flight simulator weather conditions to 700 ft overcast, cloud tops at 10,000 ft., and one mile visibility. The wind is calm.

- Move your aircraft to Chester's Runway 17, airport 3B9 (KSNC in FSX), and retract the flaps to 0°.

- Tune the Nav-1 receiver to Madison VOR, 110.4 MHz., ident MAD. Fly the first leg with Nav-1.

- Set the VOR-1 OBS to 258°. Reset the timer to zero.

- Set the Nav-1 Standby Frequency to 116.6, CMK VOR.

- Switch the DME to Nav-1 receiver.

- Tune the Nav-2 receiver to 108.8 MHz., the Bridgeport VOR, ident BDR.

- Set the VOR-2 OBS to 234° for the BAYYS intersection and the approach heading for Rwy 24.

- Fly Nav-1. Takeoff from Runway 17, Chester airport, with a climbing left turn over the airport to intercept and track 258° to MAD VOR. ATC has cleared you to 4000 ft.

- Climb at 90 kts., then cruise at 110 kts. after reaching 4000 ft.

- MAD VOR is 9 DME from Chester Airport.

- On station passage at MAD VOR, when the FROM flag appears, turn right to magnetic course 276° and set the VOR-1 OBS to 276°.

- Descend to 3000 ft. after passing MAD VOR.

- When the two VOR needles center you are at BAYYS Intersection, the Initial Approach Fix, IAF, for this approach.

- BAYYS Intersection is 12.7 DME from MAD VOR.

- Fly Nav-2. When the VOR-2 needle centers at BAYYS, turn left and track TO the BDR VOR on the 234° heading.

- Descend to 1800 ft.

- Switch the Nav-1 receiver to its Standby Frequency, 116.6 MHz; CMK VOR, ident CMK.

- Set VOR-1 OBS to 110°.

- Drop one notch of flaps and slow to 75 kts.

- MILUM intersection, the FAF for the VOR approach to Runway 24, is the intersection of the 110° radial from CMK VOR.

- On reaching the MILUM intersection and FAF, start the timer and descend to 500 ft.

- Continue tracking inbound TO the Bridgeport VOR and Runway 24.

- At 75 kts., 3 min., 45 secs. will elapse to fly the 4.7 NM. to the MAP or Runway 24 threshold.

- With one-mile visibility, Runway 24's threshold or approach lights should become visible in 2 min., 58 secs.

- Bridgeport's field elevation is 10 ft., so you will have 47 seconds to descend 490 ft. for touchdown. Slow the aircraft for a normal landing by reducing power and further lowering the flaps.

- Flight time: about 20 minutes.

* * *

This ends the VOR approaches. The next section introduces the Instrument Landing System.

Before moving on to the ILS, though, fly each approach above a second time to hone the techniques.

Click on the ILS Basics button to learn about the Instrument Landing System.

Site best viewed at 600 × 800 resolution or higher.

© 1999 – 2008, Charles Wood.